Amazon Cognito Ratelimit Bypass

Howdy folks. I am going to keep this one relatively short.

But being my first ever reported public vuln, I want to keep this for the records.

This is my journey of discovering and reporting a ratelimit bypass in one of the biggest IDPs out there.

Introduction

So lately I was doing a webpentest on a rather boring webapp. There was not much to see or do, and the most critical stuff I found was some IDOR.

Not being the webpentest Overlord, I started to look around what new shit was going on in the webpentest world and for sure stumbled upon James Kettle’s talk at Defcon and the according research over at PortSwigger. I highly recommend you read and watch that if not already done so.

The application in question was using Amazon Cognito as Identity and Access Management platform. My first thought was: “Dude it’s Amazon. For sure they are not prone to such a vulnerability”. And then I was like why not give it a try.

The Journey

Race Conditions And Rate Limits

From a security perspective you want your application to throttle requests to sensitive functions if you see them get flooded. This could be e.g. a login form, where an attacker tries to brute-force his way into the application. Best case here is that after let’s say 5 failed attempts the user needs to wait for 5 minutes until the next try can be done and / or the account get’s locked and can only be reactivated via a link send by mail / by an admin or whatever.

If the application sees that there are thousands of login requests rolling in it should lock the IP address for let’s say an hour before it accepts new connections from it.

What James did with his research was rather than sending the requests one after another, he send them in parallel. The problem to tackle was that due to things like jitter, latencies etc. even if sending those packets in parallel, they would not reach their destination at the very same time, allowing the application to still kick their restrictions in.

This resulted in his implemention of the single-byte attack which goes like this (source: Smashing the state machine):

If the request has no body, send all the headers, but don’t set the END_STREAM flag. Withhold an empty data frame with END_STREAM set. If the request has a body, send the headers and all the body data except the final byte. Withhold a data frame containing the final byte.

Next, prepare to send the final frames:

Wait for 100ms to ensure the initial frames have been sent. Ensure TCP_NODELAY is disabled - it’s crucial that Nagle’s algorithm batches the final frames. Send a ping packet to warm the local connection. If you don’t do this, the OS network stack will place the first final-frame in a separate packet.

With this approach the packets reaching the server would be completed within 1ms and less.

Please read through the research and watch the video to understand what is going on, as James is far better than me in explaining what is happening.

The Story Unfolds

My application was propperly doing rate limit restrictions and locking accounts after X failed attempts goind the normal route (which was intruder sending the requests on after the other), so initially I was not able to put that finding onto my list.

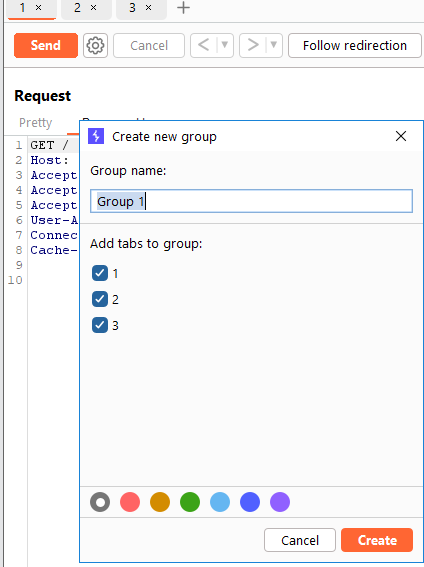

Already using Burp for the rest of the pentest I followed the examples and labs provided by PortSwigger which you can find here.

You send the login request to Repeater, duplicate your tab like 20 times, group them and then set this group to be send in parallel.

What you then might observe is that in some tabs you get a propper response and in others you get like an info that rate limiting kicked in.

Unfortunately, this was not the case here because the login resulted in a redirect which the tabs would not auto follow.

The Turbo Intruder script for this does not follow redirects either, and after talking to James it turns out that this would be rather tricky to implement.

Damn it.

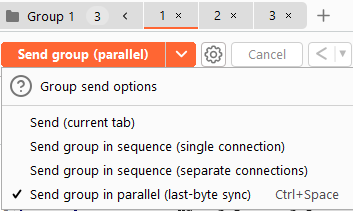

I then, just out of curiosity, send the login request to Intruder, remembering that you can set resource pools for the attack.

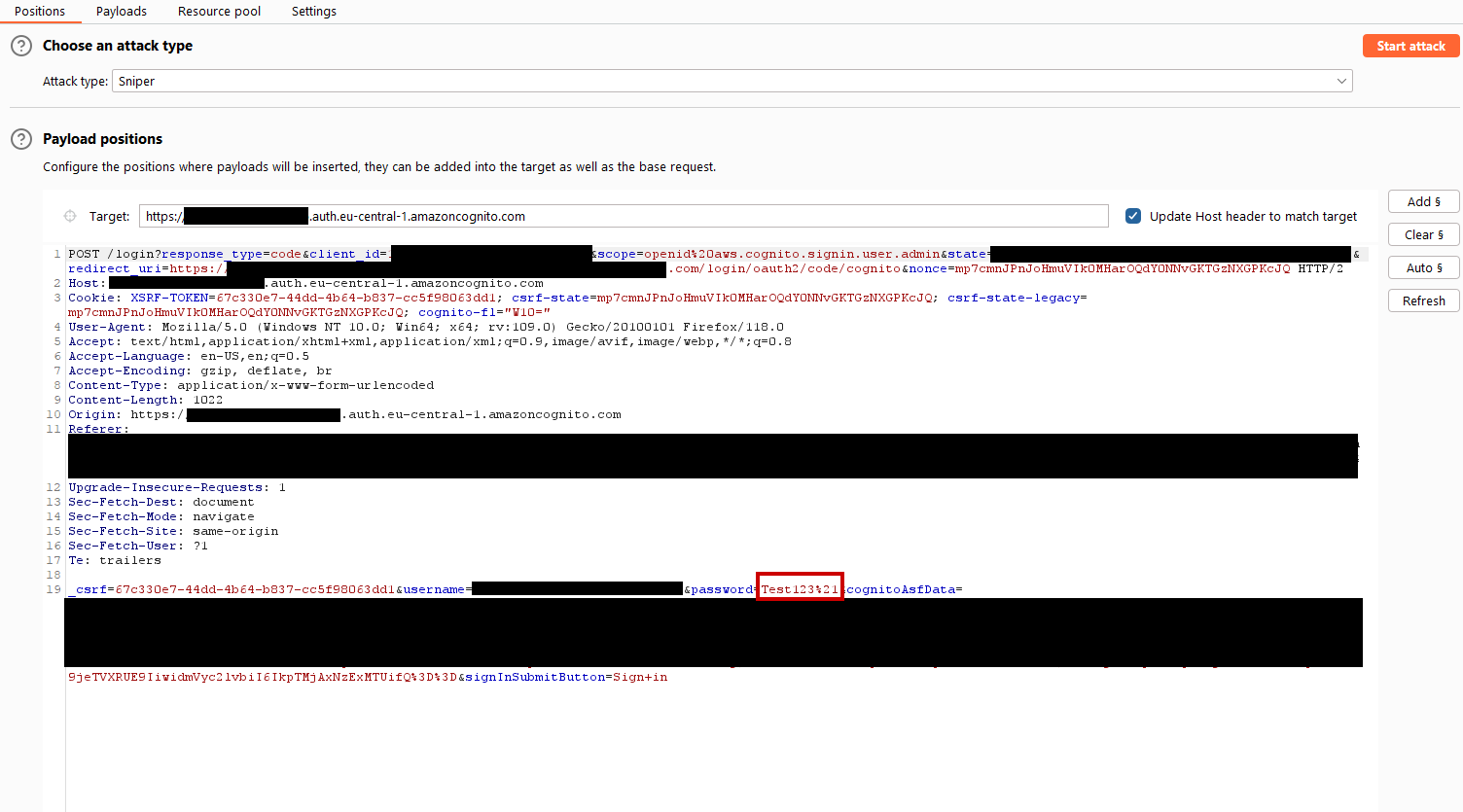

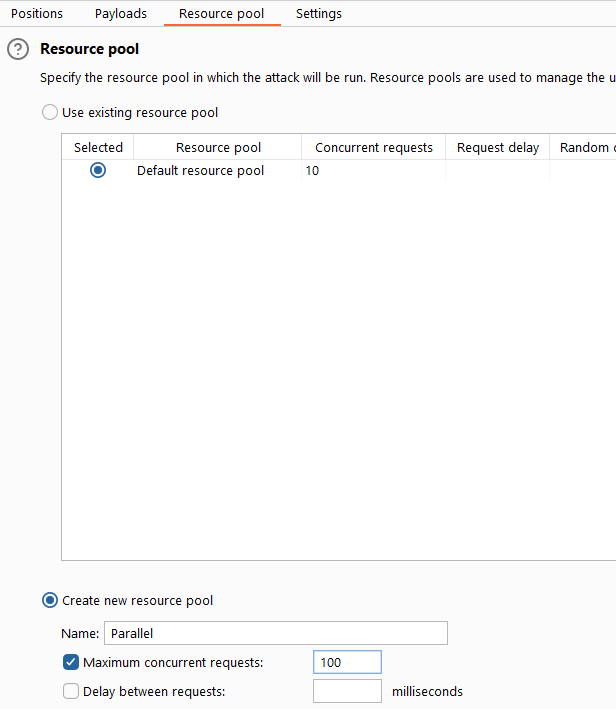

My settings within Intruder looked like this:

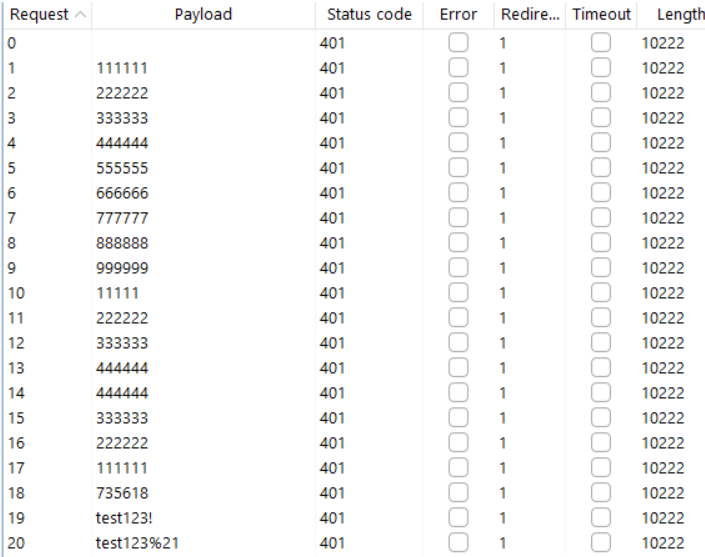

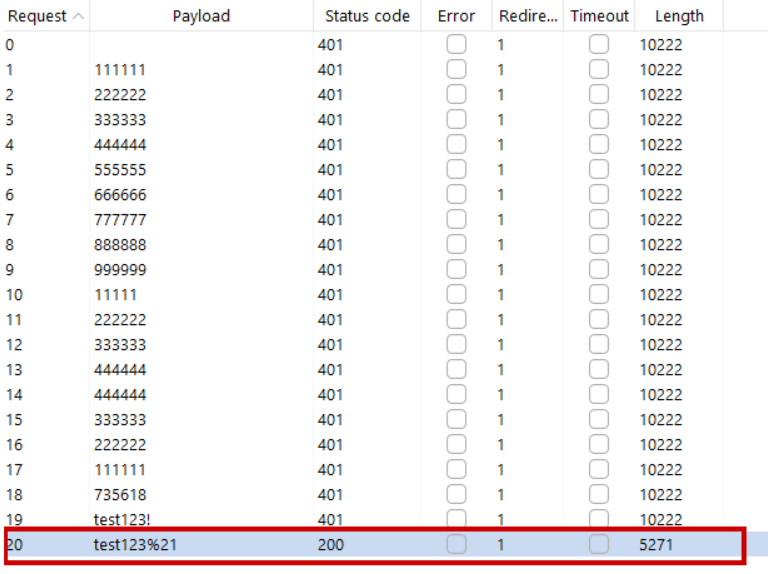

For comparison reasons I several times did the same attack with default settings / sending requests one after another and with everything in parallel. I took 20 passwords and kicked off the attack.

Sequential requests -> all 401s:

Parallel requests:

And tada:

At this time I was able to replicate the behavior over and over again, but still I struggled to believe this was a valid finding. So I reached out to James asking if he would be available for a small exchange of info, which he was. He replied with:

Hi Daniel,

Nice finding, this looks like a legitimate rate-limit bypass via race condition to me.

Wait, what!? Legit finding he said.

James also pointed me to this article from Pentagrid, who reported like a very similar issue back in 2021 which was fixed by Amazon. They actually used Turbo Intruder back then, which would nowadays no longer work out of the box. Since the complete auth flow changed, we now have redirects etc., till now no one seems to have messed with the new flows inside AWS Cognito.

Putting The Pieces Together

I looked around further and came across some really odd stuff. Besides the actual login request there is also a password reset function. Additionally all users in the app needed to have MFA in place, which was an extra request after the initial login.

Here are my findings:

-

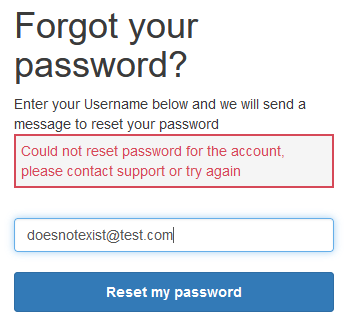

The forgot password function at

https://<REDACTED>.auth.eu-central-1.amazoncognito.com/forgotPasswordallows for user enumeration. At least this is the case with the app I tested, but I honestly do not know if this is related to a setting inside Cognito or if it is just as is (what I have seen so far from my colleagues, this is just how it is). Invalid user:

Valid user:

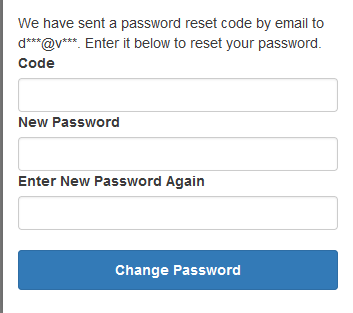

If you guessed a valid user’s mail address (can also be done with the rate limit trick), the function to reset the password at

/confirmForgotPasswordis also prone to the same rate limit attack as the login. Hence, you would theoretically be able to try to brute-force the 6 digit PIN and set a new password for a guessed user. -

The MFA flow is also prone to the rate limit bypass. So once you either guessed, brute-forced, found or whatever a correct user and password, you could again also abuse the MFA function to hack your way in.

I won’t bother you with more pictures here as it is always looking the same.

Reporting

After I was confident enough and armed with all the info needed, I contacted the AWS security team on 2023-09-20 with everything I had.

Some of the stuff shared was the attack flow:

Login:

- In a browser on the login page enter a username and a false password

- Intercept the request with Burp proxy

- The first request always goes to https://<webapp>.auth.eu-central-1.amazoncognito.com/cspreport and I just forward it

- The 2nd request is a POST request to https://<webapp>.auth.eu-central-1.amazoncognito.com/login and the POST body contains the parameters _csrf, username, password, cognitoAsfData and signInSubmitButton

- Forward this POST request to Burp Intruder

- Add injection point at the password field

- Define payloads. I did like 30-50 random words including the real password

- Set the resource pool so that Burp sends the requests in sequence

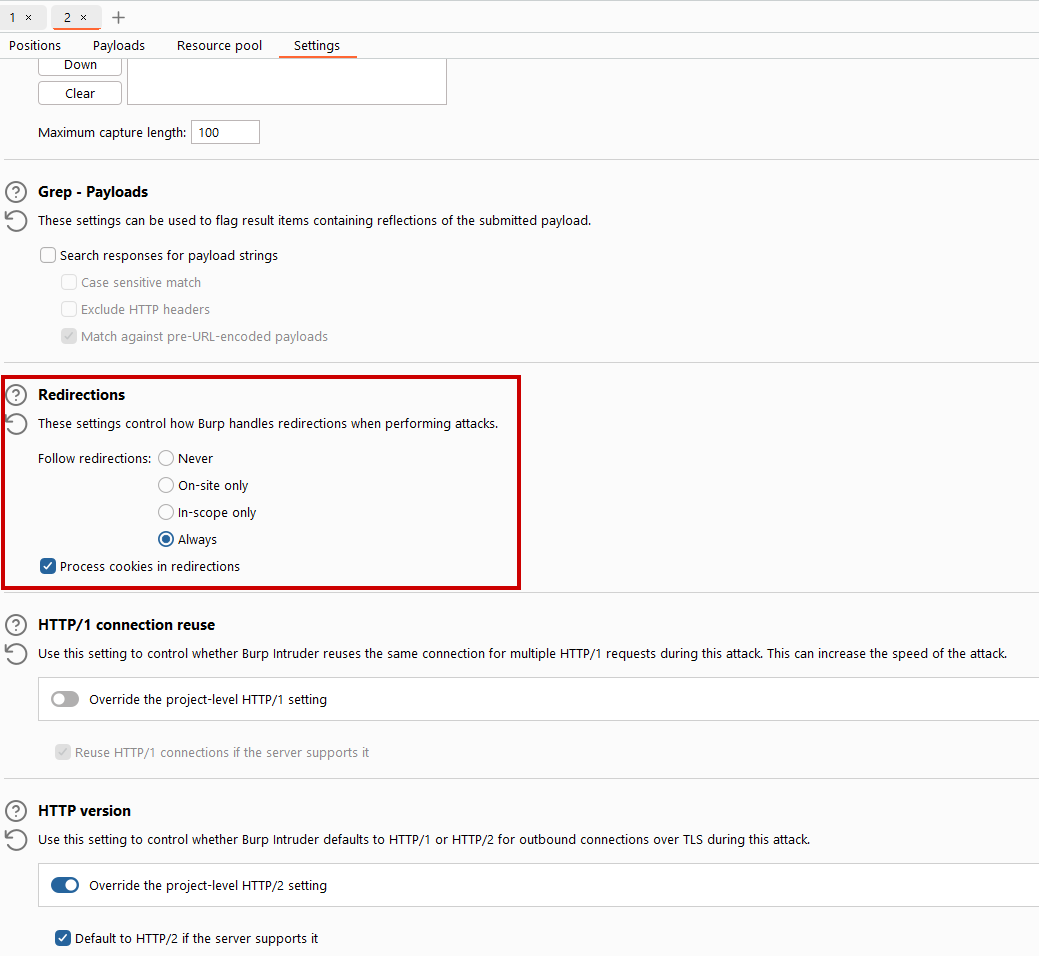

- Set the follow redirect settings to always follow redirects and process cookies

- Disable HTTP 1 settings

- Hit attack

Observation:

- The real password that is somewhere in the middle of the payloads results in the same 401 as all the other false passwords

- Cognito reacts with a warning message in the browser: "Application is buy, please try again in a few minutes."

- No clues for an attacker about the correct guess

- Rate limiting kicked in

POC:

- Change the resource pool from Burp to allow 50 requests in PARALLEL

- See that the correct password results in a 200 OK response after all redirects, rather than all false passwords still getting a 401

- See that rate limiting was successfully bypassed by sending in parallel

Strange Things

I want you to make up your own thoughts about this and try to reflect what happened as neutral as possible.

At first I was very happy with how the communication went. Everyone was very polite, responses came in rather quick.

On the 2nd of November I received the feedback for my blog post draft which I gave them. They stated that both, the Forget-Password function as well as the MFA prompt were “fixed previously” and “confirmed through manual testing” are not vulnerable. So my assumptions and statements were wrong according to AWS.

Immediately I thought: So you are telling me you knew cognito is / was prone to such attacks, and then you decided like “Hey let’s fix this in some subfunctions (MFA and Reset PW) but ignore the main login logic.”

Like really?

Also, I did the same tests on all three endpoints and all gave me the same results. You were able to reproduce this, confirmed it is a bug in the login but not the MFA or reset function???

At least this sounded very strange and not plausible to me, but this is how it went and I am not the expert to assess this in depth. And maybe I just have a wrong point of view here.

It then so happened that I asked for more details on this, and guess what … On the 29th of November I got an update email saying they did some more testing and now they also see that the MFA flow is prone to the attack, however the Forgot-Password function still is not.

At this point I just replied that this thing is getting weirder the more often we have a conversation about it, but that it is up to them to handle this case and their product.

I also reflected it internally and involved our team responsible for the product.

I also asked AWS if I / they could give out some pre-notification (without any details) to customers / public to warn them about the current state so that they would be able to at least monitor their logs and act if adversaries would abuse this.

The answer to that was: “Notifying affected customers is part of our mitigation and disclosure processes.”

Well, at least we did not receive any sort of info, that there might be a problem, as a customer until today.

On the 18th of December we then happened to have an official call with like 10 people. AWS assured that they take security seriously, that they are pushing hard on getting everything fixed and rolled out (hopefully that week we talked) and that some miscommunication might have occured in the course of events which they want to address internally.

The self requested 90 days period ended on the 19th of December and there was no single info from AWS since our call.

So I once again reached out to my contact at AWS on the 27th of December to ask about the current state and if I could release the blog post. Got a reply the same day that they are sorry for the delay again. The fix is globally deployed and I am good to make things public.

I can haz CVE?

Unfortunately I can’t.

I provided all the details to the Mitre CNA, but they replied that SaaS is not covered by CVEs, hence -> NOPE.

I really was exited for this being my first ever CVE for the records, but it should just not have happened.

Timeline

2023-09-18: Discovery of the issue

2023-09-20: First contect with AWS Security team

2023-09-20: Same day response from the AWS Security team asking for more detail and step-by-step attack flow

2023-09-21: My reply with all questions answered. Also asked if they issue a CVE if applicable and if okay to write a blog about it

2023-09-21: Reply from AWS Security that they are investigating on my report. They would issue a CVE if appropriate and would like to see my blog post before release

2023-09-28: AWS Security saying they are still investigating and will keep me updated

2023-09-29: My reply that I am fine with that and they should take their time

2023-10-15: Me asking for an update on the case

2023-10-16: AWS Security saying they are in the process of developing a fix for the problem and would like to see my blog post

2023-10-17: Me asking questins about handover of the blog and status on CVE

2023-10-17: AWS details how to handover the blog and says GHSA / CVE is evaluated after fix is complete

2023-10-18: Me sending over my blog draft

2023-11-02: AWS shared commented blog. There are only two statements and that state that the PW-Reset nor the MFA function have been fixed BEFORE my report. They also ask for my disclosure timeline. They want to have the fix ready before 90 days pass.

2023-11-06: Me asking why someone who knows there is a vuln would patch two subfunctions but not the main login logic. I agree to the 90 days timeline for disclosure.

2023-11-06: AWS states a subject matter expert will answer my open questions regarding the patching

2023-11-10: Me asking if I or they can do like a pre-notification to all customers, so they can at least monitor their logs for suspicious activity until a fix is available

2023-11-10: AWS states that this is part of their mitigation and siclosure process. They ask me to not anounce anything until the 90 days period.

2023-11-15: Me asking for the affected version numbers and an update on my questions regarding patching

2023-11-16: AWS states they are still working on a fix. They are not giving me the version number, but rather state that the fixed version has not been merged… . The info regarding my question for the patch are the same as last time.

2023-11-17: Me asking again for affected versions and the statement from the subject matter expert to clarify on plausibility of their statements

2023-11-29: AWS states they are still targeting the end of December for a fix. They now also say that the login AND MFA implementation are affected and only the forget password stuff is not.

2023-11-30: Me replying that I will stick to my word with the 90 days period. I also mention that this gets more weird the more we talk about it, but that it’s up to them to handle their product.

2023-12-18: Official call with AWS assuring they are always like security 1st and will do everything to fix this. The initial false assumption regarding the flaws was a miscommunication topic.

2023-12-27: Asking for an update on the current situation.

2023-12-27: AWS is sorry for the delay. Fix is rolled out and I am good to release my blog.

Wrap up

So there goes my very first ever reported vulnerability and I have mixed feelings about it.

Why is such a huge company not up to date with current vulnerability research?

Why so many turns in what is vulnerable and what is not?

What other services might be impacted out there by other big (and also little) players?

Why no bug bounty program if you seemingly can’t handle it internally?

Don’t get me wrong, I am not to blame anybody here, but it think there is room for improvement - internally as well as with the interaction with security researchers. This blog is reflecting MY view and feelings on the whole situation, and to get the whole picture you should always listen to all parties involved.

I would always act the same way, even knowing how the process might look like. I am here to make the world a safer place, and that was my contribution to it.

Acknowledgement

I absolutely want to mention James Kettle here once more, as this was all his heavy lifting up front with his research, and I am just a lame leecher. He was very kind and willing to help, too.

I also want to thank the AWS security team. Although the whole process left me with mixed feelings, the overall experience was more on the positive side.

Last but not least my current company Vorwerk and especially my team, who allow me to dig into such topics as part of my work. You can thank them if the fix now covers your asses :)

Have a nice day

Cheers Dan